[Kinda full book review]

Searching for a sort-of definitive guide on wine-cheese pairing, your intrepid reviewer came across Tasting Wine & Cheese, by Adam Centamore. Browsing through, scepticism started, to be returned to optimism in the introductory chapters. That are quite basic, but with hints of systematic treatment of the subject. And, given the introductory level, miss a few ‘rules’ here and there, in the wine, in the cheese, and in the wine-cheese sections.

Like, what grows together, goes together – yes that is mentioned twice in the book, but elsewhere, piecemeal. Yes, the introduction is about experimenting. Which is what one does when having more experience. If the book is for readers that want to jump into the experimentation, why is the introduction so simple and except a few without systematic rules? If the book is for beginners, why jump to experimentation without first handling the basic thoroughly? And then have near the end of the book with some (…) classic wine-cheese (and –codiment) combinations that all are (some of) the very grow together things that could have been treated upfront. Or in all chapters, where ‘the cheese that loves it’ typically is not from the same area. Often, because some American cheese is mentioned that, like many European brands (yes, often not types only but specific brands that very often can’t be had locally), will be available only here and there. Mostly there.

Except Stilton and port – the Anglophile angle on ‘grow together’, overlooking history where port and Dutch cheeses were styled together when anything out of France was impossible to have at the other side of the Channel. Yes, grows together is a way in which centuries of careful crafting of wines and cheeses to make the perfect fit is captured, so why not have this as the foundation for variation?

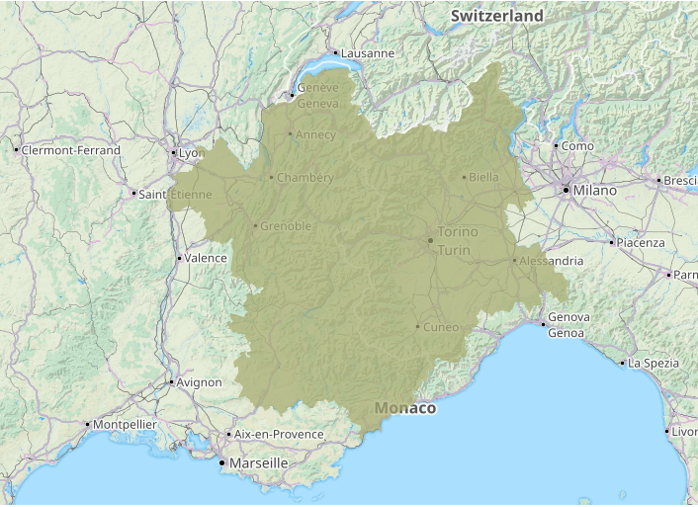

Except where Langres is thought ideal for Champagne. Yeah, if you mistake (fact) Langres for being in the Champagne instead of being between the utterly Bourgogne Chablis and the Côte d’Or. Like Durango is in Arizona because it’s close to the Four Corners. One, Langres isn’t in the Champagne of the wines nor of the département; two, Chaource comes from much closer, and is indeed the better pairing. Now, Chaource is mentioned but with Crémants in general where (with the better wines) Langres would be ideal. Why? Noting that with Chaource, having some Champagne in the fontaine makes the pairing outright sublime, yes.

There’s quite a number of outright errors as well. Just browsing around a little, far from complete:

Champagne can only be made of the three grapes ..? Foolish mistake, legally and practically; e.g., the Champagnes with Pinot Blanc that are resurfacing, have funky edges that are perfect for surprises and horizontal tastings. Not to mention Arbane, Pinot Gris and Petit Meslier. Blanc de Noirs being only from Pinot Noir? That’s just stupid. Forgetting to mention the tangerine edge of Noirs, in particular from the Meunier (try a Württemberger Lemberger or a still red from the Champagne and you’ll know), also doesn’t convey much experience with Champagnes outside the annual-million-bottle factory produce of the big companies. Wouldn’t call them ‘houses’, reserve that for the small sometimes artisanal honest producers.

White wine, even when crisp, at 4.4° to 10° …? Wine for which that is ideal, isn’t worth much is it?

Riesling not grown in France ..? Hello, Alsace! Yes tacos will not be served anywhere in Texas because it has in history never belonged to Mexico, right? Alsatian Riesling may have different characteristics but when declared not to exist, how can one tell ..?

Bell pepper aroma (a.k.a paprika everywhere except some local i.e. ‘American’ regions) is mentioned as a characteristic “often found” Cab Sav (p. 147). Right. When your Cab Sav (p.110, can anyone explain the out of order of the Tempranillo and Cab Sav in this section?) has paprika notes, it is not well-crafted, it is very-badly-crafted. Paprika is known to be an indication of serious errors in the making of the wine except in wines with clear Cab Franc influence or dominance and even then. Cab Franc badly made: Green paprika, biting. Cab Franc well-made (e.g., the Canadian ones! Try a Fort Berens or a Burrowing Owl and you’ll know): Mellow yellow paprika, perfect!

[And then one encounters the very rare Frappato brand one has on stock. Other Valle dell’Acate’s are much more interesting. Take a Cerasuolo de Vittoria, excellent on its own but with what cheese ..?]

In general, the wine characteristics are unhelpful as they are either either-or qua style, or incomplete. As mentioned on pp. 88-91 and many places elsewhere, the variety outstretches most of the ‘characteristics’—then why pick a few? And the wines list itself is very incomplete, slightly erratic, as well.

Also I expected to have a good cheese list with wine suggestions as well, not the accidental index lookup. What’s there now, is random examples as if not cheesemakers from some same region make cheeses that are as different from their neighbour’s as what winemakers make.

“In the end, though, pairing cheese and wine is an inexact science, if a science at all.” This, halfway through the book (p.85) so how’s that for in the end, seems to summarise the book quite well. Though one remains unconvinced the author actually intended the self-reference.

Is this book for beginners that need to learn the bars and chords and some simple music pieces, or is it for a seasoned jazz musician? One is lead to believe, both. Starting and ending with general tips & tricks is for the former. But the bewildering details suddenly without too many basics will throw off the beginners, and the lack of systematic treatment (jazz musicians train their bars much more often than beginners..!) will throw off the jazz musician.

Concluding: Not the definitive, systematic wine-cheese and cheese-wine pairing guide I was looking for. Not the guide you should be looking for, either.

We’ll rest with:

[Bayeux is just (?) over the edge of Camembertland, so still perfect with cider – not in the book]