[From the brewery, towards the future]

[From the brewery, towards the future]

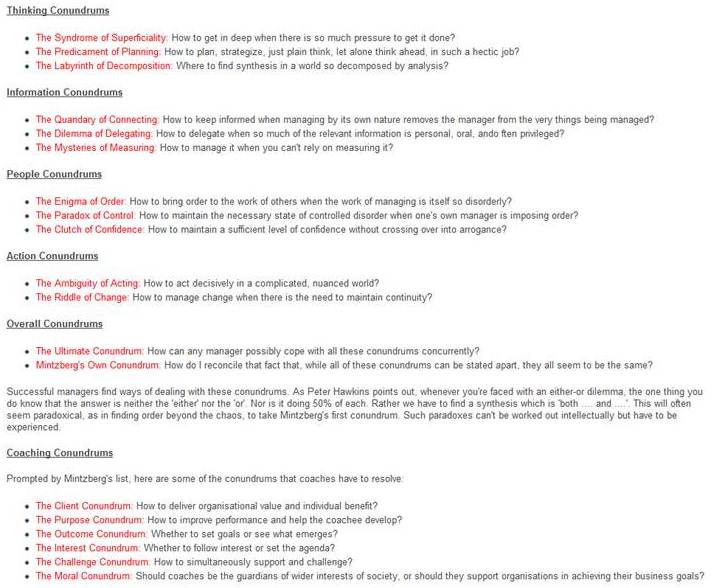

The second ‘Book By Quote‘ then

(An attempt to subjectively summarise a book by the quotes I found worthwhile to mark, to remember. Be aware that the quotes as such, aren’t a real unbiased ‘objective’ summary; most often I heartily advise to read the book yourself..!)

So, this time: Jaron Lanier’s Who Owns The Future, Simon&Schuster, May 2013, ISBN 9781451654967

Moore’s Law means that more and more things can be done practically for free, if only it weren’t for those people who want to be paid. (p.10)

A heavenly idea comes up a lot in what might be called Silicon Valley metaphysics. We anticipate immortality through mechnization. (p.12)

I remember the thrill of using military-grade stealth just to argue about who should pay for a pizza at MIT in 1983 or so. (p.14)

We’ve decided not to pay most people for performing the new roles that are valuable in relation to the latest technologies. Ordinary people “share,” while elite network presences generate unprecedented fortunes. (p.15)

Basics like water and food could soar in cost even as intensely sophisticated gadgets, like automated nanorobotic heart surgeons, float about as dust in the air in case they are needed, sponsored by advertisers. (p.18)

Digital technology changes the way power (or an avatar of power, such as money or political office) is gained, lost, distributed, and defended in human affairs. Lately, network-empowered finance has amplified curruption and illusion, and the Internet has destroyed more jobs than it has created. (p.19)

Information needn’t be thought of as a freestanding thing, but rather as a human product. It is entirely legitimate to understand that people are still needed and valuable even when the loom can run without human muscle power. It is still running on human thought. (pp.22-23)

Information storage was reserved for only a few special topics, such as laws and stories of kings and divinity. And yet debt made the cut. (p.29)

Any information technology, from the most ancient money to the latest cloud computing, is based fundamentally on design judgements about what to remember and what to forget. Money is simply another information system. (p.32)

Winner-takes-all contests should function as the treats in an economy, the cherries on top. To rely on hem fundamentally is a mistake – not just a pragmatic or ethical mistake, but also a mathematical one. (p.40)

While some critics might have aestetic or ethical objections to winner-takes-all outcomes, a mathematical problem with them is that noise is amplified. Therefore, if a societal system depends too much on winner-takes-all contests, then the acuity of that system will suffer. It will become less reality-based. (p.41)

To get a bell curve of outcomes there must be an unbounded variety of paths, or sorting processes, that can lead to success. That is to say there must be many ways to be a star. (p.42)

Star systems starve themselves;

Bell curves renew themselves.

(p.42)

Middle-class levees came in many forms. Most developed countries opted to emphasize government-based levees,… None of these were perfect. None sufficed in isolation. A successful middle-class life typically relied on more than one form of levee. And yet without these exceptions to the torrential rule of the open flow of capital, capitalism could not have thrived. (pp.44-45)

Markets are an information technology. A technology is useless if it can’t be tweaked. If market technology can’t be fully automatic and needs some “buttons,” then there’s no use in trying to pretend otherwise. You don’t stay attached to poorly performing quests for perfection. You fix bugs. And there are bugs! We just went through taxpayer-funded bailouts of networked finance in much of the world, and no amount of austerity seems enough to fully pay for that. So the technology needs to be tweaked. Wanting to tweak a technology shows a commitment to it, not a rejection of it. (p.45)

Very few rich people are strictly big earners. There are a few in sports or entertainment, but they are freakish anomalies, economically speaking. Rich people typically earn money from capital. (p.46)

What might be called “upper-class levees,” like exclusive investment funds, have been known to blur into Ponzi schemes or other criminal enterprises, and the same pattern exists for levees at all levels. … Whether for the rich or the middel class, levees are inevitably a little conspirational, and conspiracy naturally attracts corruption. (p.48)

Before the networking of everything, there was a balance of powers between levees and capital, between labor and management. The legitimizing of the levees of the middle class reinforced the legitimicy of the levees of the rich. A symmetrical social contract between nonequals made modernity possible. … Finally the middle-class levees were breached. One by one, they fell under the surging pressures of superflows of information and capital. (p.49)

The principal way a powerful, unfortunately designed digital network flattens levees is by enabling data copying. When copying is easy, there is almost no intrinsic scarcity, and therefore market value collapses. (p.50)

If you never knew the music business as it was, the loss of what used to be a significant middle-class job pool might not seem important. I will demonstrate, however, that we should perceive an early warning for the rest of us. (p.51)

In each case, someone is practically blackmailed by the distortions of playing the pawn in someone else’s network. It’s a weird kind of stealth blackmail because if you look at what’s in front of you, the deal looks sweet, but you don’t see all that should be in front of you. (p.61)

A Siren Server, as I will refer to such a thing, is an elite computer, or coordinated collection of computers, on a network, It is characterized by narcissism, hyperamplified risk aversion, and extreme information asymmetry. (p.54)

Put another way, the new schemes, the Siren Servers, channel much of the productivity of ordinary people into an informal economy of barter and reputation, while concentrating the extracted old-fashioned wealth for themselves. (p.57)

Differential pricing is worthy of attention only because of its starkness. Even if differential pricing turns out to be rare, the key point is that it’s hard for ordinary people who interact with Siren Servers to get enough context to make the best decisions. If not differential pricing, then some other scheme will appear in order to take advantage of information asymmetry. After all, that is what information assymetry is for. (pp.63-64)

The terminology of “disruption” has been granted an almost sacred status in tech business circles. It is ordinary for a venture capital firm to advertise that it is seeking to fund business plans that “shrink markets.” To disrupt is the most celebrated achievement. In Silicon Valley, one is always hearing that this or that industry is ripe for disruption. We kid ourselves, pretending that disruption requires creativity. It doesn’t. It’s always the same story. (p.66)

“Disruption” by the use of digital network technology undermines the very idea of markets and capitalism. Instead of economics being about a bunch of players with unique positions in a market, we develop towards a small number of spying operations in omniscient positions, which means that eventually markets of all kinds will shrink. (p.67)

The information economy that we are currently building doesn’t really embrace capitalism, but rather a new form of feudalism. (p.79)

Without the public road, and utterly unencumbered access to it, a child’s lemondae stand would never turn a profit. The real business opportunity would be in privatizing other people’s roads. Similarly, without an open, unified network, the whole notion of business online would have been entirely feudal from the start. Instead, it only took a feudal turn around the turn of the century. (p.87)

A pattern has emerged in which holders of academic posts related to Internet studies tend to join in the acceptance or even the celebration of the decline of the creative classes’ levees. This strikes me as an irony, or an anxious burst of denial. Higher education could be Napsterized and vaporized in a matter of a few short years. In the world of the new kind of network wealth, towering student debt has become yet another destroyer of the middle classes. (p.92)

Is it a coincidence that formal education is starting to become impossibly, cosmically expensive just at the moment that informal education is starting to become free? No, no coincidence. This is just another little fractal reflection of the big picture of the way we’ve designed network information systems. The two trends are a single trend. (p.96)

Occasionally an objective test of big business data reveals that the castles in the clouds were never real. For instance, there is no end to the braggadocio of a social network trying to sell advertising. The salespeople trumpet their system’s ability to minutely model and target consumers as if they were Taliban in the crosshairs of a military drone. And yet, the same service, when it must simply detect if a user is underage, will turn out to be unable to counter the deceptions of children. (p.114)

When correlation is mistaken for understanding, we pay a heavy price. An example of this type of failure was the string of early 21st century financial crises in which correlations created gigantic investment packages that turned out to be duds in aggregate, bringing the world to indebtness and austerity. (p.115)

A wannabe Siren Server might enjoy honest access to data at first, as if it were an invisible observer, but if it becomes successful enough to become a real Siren Server, then everything changes. A tide of manipulation rises, and the data gathered becomes suspect. If the server is based on reviews, many of them will suddenly become start to be fakes. If it’s based on people trying to be popular, then suddenly there will be fictitious fawning multitudes inflating illusions of popularity. If the server is trying to identify the most creditworthy or datable individuals, expect the profiles of those individuals to be mostly phony. (p.116)

Nine dismal humors of futurism, and a hopeful one

• Theocracy: Politics is the means to supernatural immortality

• Abundance: Technology is the means to escape politics and approach material immortality

• Malthus: Politics is the means to material extinction

• Rousseau: Technology is the means to spiritual malaise

• Invisible Hand: Information technology ought to subsume politics

• Marx: Politics ought to subsume information technology

• H.G. Wells: Human life will be meaningful because primordial, pretechnological tribal drama will be reinstated once we are sufficiently challenged by either our own machines or by aliens. So, technology creates human meaning through challenge rather than through providing Abundance

• Strangelove: Some person will destroy us all when technology gets good enough. Human nature plus good technology equals extinction

• Turing: Politics and people won’t even exist. Only technology will exist when it gets good enough, which means it will become supernatural

• Nelson: Information technology of a particular design could help people remain people without resorting to extreme politics when any of the other, creepily escatological humors seem to be imminent.

(pp.124-128)

The obvious figurehead for this humor is Rousseau, but E.M. Forster could also serve as the cultural marker for nostalgic technophobia because of his short story “The Machine Stops.” This was a remarkably accurate description of the Internet published in 1909, decades before computers existed. To the dismay of generations of computer scientists, the first glimmer of the wonders we have built was a dystopian tale. In the story, what we’d call the Internet is known as the “Machine.” The world’s population is glued to the Machine’s screens, endlessly engaged in social networking, browsing, Skypeing, and the like. Interestingly, Forster wasn’t cynical enough to foresee the centrality of advertising in such a situation. At the end of the story, the machine does indeed stop. Terror ensues, similar to what is imagined these days from a hypothetical cyber-attack. The whole human world crashes. Survivors straggle outside to revel in the authenticity of reality. “The Sun!” they cry, amazed at luminous depths of beauty that could not have been imagined. The failuer of the Machine is a happy ending. (p.129)

Marx also described a subtler problem of “alienation,” a sense that one’s imprint on the world is not one’s own anymore when one is part of someone else’s scheme in a high tech factory. Today there is a great deal of concern about the authenticity and vitality of live lived online. Are “friends” really friends? These concerns are an echo of Marx, almost two centuries later, as information becomes the same thing as production. (p.137)

But in order for a computer to run, the surrounding parts of the universe must take on the waste heat, the randomness. You can create a local shield against entropy, but your neighbors will always pay for it. (p.143)

Systems with a lot of peaks must also have a lot of valleys between the peaks. When you hypothesize better solutions to today’s way of dealing with complex problems, you are automatically also hypothesizing a lot of new ways to fail. (p.151)

Google might eventually become an ourobouros, a snake eating its own tail, unless something changes. This would happen when so many goods and services become software-centric, and so much information is “free,” that there is nothing left to advertise on Google that attracts actual money. Today a guitar manufacturer might advertise through Google. But when guitars are someday spun out of 3D printers, there will be no one to buy an ad if guitar design files are “free.” (p.154)

You mustn’t demand that someone be able to state exactly how information underrepresents reality. The burden can’t be on people to justify themselves against the world of information. (p.161)

Sirenic enterpreneurs intuitively cast free will – so long as it is their own – as an ever more magical, elite, and “meta” quality of personhood. The enterpreneur hopes to “dent the universe” or to achieve some other heroic, Nietzschean validation. Ordinary people, however, who will be attached to the nodes of the network created by the hero, will become more effectively mechanical. (p.166)

Making choices of where to place the barrier between ego and algorithm is unavoidable in the age of cloud software. Drawing the line between what we forfeit to calculation and what we reserve for the heroics of free will is the story of our time. (p.168)

Every tale of adventure lately seems to include a scene in which characters are attempting to crack the security of someone else’s computer. That’s the popular image of how power games are played out in the digital age, but such “cracking” is only a tactic, not a strategy. The big game is the race to create ascendant Siren Servers, or, much more often, to get close to those that are taking off and ascending in ways that no one predicted. (p.175)

This is a key sign of a Siren Server. The lowly non-Sirens are responsible as possible, while the Siren Server presides from an arm’s length. (p.176)

The ideal Siren Server is one for which you make no specific decisions. You should do everything possible to not do anything consequential. Don’t play favorites; don’t have taste. You are to be the neutral facilitator, the connector, the hub, but never an agent who could be blamed for a decision. Reduce the number of decisions that can be pinned to you to an absolute minimum. What you can do, however, is pattern how other people make decisions. (p.184)

Competition becomes mostly about who can out-meta who, and only secondarily about specialization. (p.188)

We pretend that an emergent meta-human being is appearing in the computing clouds – an artificial intelligence – but actually it is humans, the operators of Siren Servers, pulling the levers. (p.191)

These algorithms do not represent emotions or meaning, only statistics and correlations. (p.192)

The argument can become more complicated, in that there are limited information bandwidths between different levels of description in the material world, so that on might identify dynamics at a gross level that could not be described by particle interactions. But the grosser a process is, the more it becomes subject to differing interpretations by observers. (p.196)

For instance, activists use social media to complain about lost benefits and opportunities, but social media (as we currently know it, organized around Siren Servers) also gradually concentrates capital and shrinks opportunities for ordinary people. Within a democracy, the resulting increased income concentration gradually enriches an elite, which is likely to promote candidates who will support yet further concentration. (p.201)

Democracy relies on laws that impose diversity on a market-like dynamic that might otherwise evolve toward monopoly. (p.202)

From the orthodox point of view, the Internet is a melodrama in which an eternal conflict is being played out. The bad guys in the melodrama are old-fashioned control freaks like governement intelligence agencies, third-world dictators, and Hollywood media moguls, who are often portrayed as if they were cartoon figures from the game Monopoly. The bad guys want to strengthen copyright law, for instance. Someone trying to sell a movie is put in the same category as some awful dictator. The good guys are young meritorious crusaders for openness. They might promote open-source designs like Linux and Wikipedia. They populate the Pirate parties. The melodrama is driven by an obsolete vision of an open Internet that is already corrupted beyond recognition, not by old governments or industries that hate openness, but by the new industries that oppose those old control freaks the most. (pp. 205-206)

You might further object that it’s all based on individual choice, and that if Facebook wants to offer us a preferable free service, and the offer is accepted, that’s just the market making a decision. That argument ignores network effects. Once a critical mass of conversation is on Facebook, then it’s hard to get conversation going elsewhere. What might have started out as a choice is no longer a choice after a network effect causes a phase change. After that point we effectively have less choice. It’s no longer commerce, but soft blackmail. (p.207)

A world in which more and more is monetized, instead of less and less, could lead to a middle-class-oriented information economy, in which information isn’t free, but is affordable. Instead of making information inaccessible, that would lead to a situation in which the most critical information becomes accessible for the first time. (p.210)

Universal retention of provenance without commensurate universal commercial rights would lead to a police/surveillance state. Universal commercial provenance can instead lead to a balanced future, where a middle class can thrive with proportional political clout, and where individuals can invent their own lives without being unduly manipulated by unseen operators of Siren Servers. Instead of relying on dubious prohibitions to avoid disasters of privacy violation or coercion, the expense of using data would temper extreme exploitation. (p.246)

If the information economy is to evolve on its present track, so that each player is either running a Siren Server or is an ordinary person ricocheting between two extremes of noncapitalism, between fake free and fake ownership, then markets will eventually shrink and capitalism will collapse. (p.247)

The Internet might have started out making better use of the public sphere, but in the 1970s and 1980s the mostly young men building what would turn into the Internet were often either potsmoking liberals or CB-radio-using, police-evading conservatives who were violating speed limits. (That’s a bit of an exaggeration, but not by much.) Both camps thought anonymity was the essence of coolness, and that it was wrong for the government to have a list of citizens, or for people to need government IDs. In retrospect I think we were all confusing the government with our parents. (p.249)

It once seemed unthinkable that tech giants like Silicon Graphics could disintegrate. If Facebook starts to fail commercially, suddenly people all over the world would be at risk of losing old friends and family ties, or perhaps critical medical histories. (p.250)

Any society that is composed of real biological people has to succeed at providing a balance to the frustrations of biological reality. There must be economic dignity, defined here as knowing you won’t fall off a cliff into abject poverty if you get sick, become a parent, or grow old. (p.253)

As I complained earlier, I hear this infuriating comment all the time: “If a lot of ordinary people aren’t earning much in today’s markets, that means they have little of value to offer. You can’t intervene to create the illusion that they’re valuable. It’s up to people to make themselves valuable.” Well, yes, I agree. I don’t advocate making up fake jobs to create the illusion that people are employed. That would be demeaning and a magnet for fraud and corruption. But network-oriented companies routinely raise huge amounts of money based precisely on placing a value on what ordinary people do online. It’s not that the market is saying ordinary people aren’t valuable online; it’s that most people have been repositioned out of the loop of their own commercial value. (p.257)

Now is when I expect to hear that this kind of activity is all fluff and not the stuff of an economy. Once again, why is it fluff if it’s for the benefit of the people who do it, while it’s real value if it’s for the benefit of a distant central server? (p.259)

Big companies are the flywheels and ballast of a market economy, creating a degree of stability. (To put it in geekspeak, they act as lowpass filters.) The resulting lessened turbulence will always annoy the most peripatetic and impatient young innovators, but it also makes it easier for most people in most phases in life to understand and navigate the economic environment. (p.266)

Advertising was one of the main business plans of the age of mass media from well before the appearance of digital technology, and there is no reason to expect it to disappear as technology evolves. In fact, advertising ought to be celebrated for the starring role it played – for centuries – in the onset of modernity. Ads romanticized progress. Advertising counterbalances the tendency of people to adhere to familiar habits. (p.267)

We will never know for sure in advance how valuable a particular datum might turn out to be. Each use of data will determine a fresh valuation of it in context. … There is no such thing as calculation without data. Therefore, if the provenance of the data has been preserved, then calculations can generally be expanded to yield additional results about who should get credit for making them possible. (p.271)

In physicality, it isn’t unusual to see puppies or large items offered fro free, because it’s hard for the owner to keep them. Thta’s almost never the case for information. There should be far less free stuff in an information economy than in physicality. (p.272)

Code would remember the people who coded each line, and those people would be sent nanopayments as part of code execution. … The Google guys would have gotten rich from the search code without having to create the private spying agency. (p.272)

Each price will have two components, called “instant” and “legacy.” … The “instant” part of the price will arise from agreement between buyer and seller. … The “legacy” portion of the price will be composed of algorthmic adjustments to instant pricing that uphold the social contract and economic symmetry. (pp.272-273)

This brings us to the “instant” part of the calculation of the nanopayment to you. It should be proportional to both the importance of the data that came from your state or behavior and what the seller downstream was able to earn and whatever profit you or your decision reduction partner tried to extract. (p.275)

The most basic attribute of a digital network is what is remembered and what is forgotten. In other words, what is entropic about the network? (p.277)

Internet commerce has evolved with the benefit of a number of free rides that create the illusion that somebody else can always pay for the non-hits, and that we should only have to pay for the hits. … That way of thinking leads to plutocracy and stagnation. In a real market, players invest in a variety of bets to cope with uncertainty. (p.278)

One of the Airbnb founders wrote on the company blog that the good experiences of millions of transactions shouldn’t be discounted because of a few bad ones. People are basically good, he decried. I agree that people are mostly good, and yet, in a functioning economy, it is necessary that those millions of good transactions account for the effects of fools, creeps, and just plain randomness. This is how money has to work if it’s to be about the future at all. Criminals and creeps are rare, but the sum of risk is unavoidable. We like to imagine ourselves as being eternally young, and flowing about in a world of trust. A perfect world, without the tragedy of the biological life cycle, without risk, could run on trust, and wouldn’t need an economy. (pp.279-280)

If the risk pool is the size of the whole society, then it isn’t really a risk pool at all. This is what happens with Google, Facebook, networked finance, and the other Siren Server schemes. This is precisely the Local/Global Flip. If each person must be her own risk pool, then we are also back where we started. Then everyone would have to sing for each supper. Material dignity and the middle class would be lost. Risk pools only become meaningful when they are bigger than individuals but smaller than the whole society. (p.280)

Cash allows us to interact without having to reveal everything. Fluid online economics is currently designed for one-sided revelation, however. (p.285)

You shouldn’t be able to sample everyone else’s stuff for free while being paid for your stuff. That’s what Siren Servers do today, and the whole point of a humanistic economy would be to get away from that pattern. (p.285)

A humanistic economy would extend the type of calculation already taking place and make it symmetrical. Therefore the same rules of assessment applied to one party in an online transaction would be applied to all other parties. (p.286)

In isolation, economic symmetry might pose a risk of a race to the bottom. Wouldn’t everyone initially want stuff for free, and then never be able to compete with the expectation of free stuff from others in order to start charging? (p.288)

In what sense is becoming dependent on private spy agencies crossed with ad agencies, which are licensed by us to spy on all of us all the time in order to accumulate billions of dollars by manipulating what’s put in front of us over supposedly open and public networks, a way of defeating elites? And yet that is precisely what the “free” model has meant. (p.291)

What about someone who can’t help but be a failure in the terms of the market place? What’s it like to be a bum in a highly advanced technological world? We don’t know yet. Computation can’t work miracles. If there is a limited space in a city center, an algorithm can’t whip up a new fold in space-time to make room for someone who doesn’t want to pay rent but still wants to live there. (p.292)

All three creepy vexations – privacy, identity, and security – have ancient pedigrees but have been made catastrophically more confusing by big data and network effects. (p.305)

Some of the most visible and immediately annoying instigators of creepiness are criminals and vandals. To my mind, however, tha actions of legitimate corporations and governments are often not far removed from those of hooligans on the creepiness spectrum. (p.306)

The creepiness problem is basically that most people aren’t idiot savants. … Only the smartest people can make no sound in the digital forest. (p.306)

The devil you know is probably not as scary as the one you don’t. (p.308)

Machine vision has massive creepiness potential. Weren’t wars fought and many lives lost precisely to prevent governments from gaining this kind of power, knowing where everyone is all the time? And yet now, because of some cultural trends, we’re suddenly happy to offer exactly the same power to a few companies in California, along with whoever will come along with enough money to piggyback on them. (p.310)

No, what we have to look at is economic incentives. There can never be enough police to shut down activities that align with economic motives. This is why prohibition doesn’t work. No amount of regulation can keep up with perverse incentives, given the pace of innovation. This is also why no one was prosecuted for financial fraud connected with the Great Recession. (p.311)

The long-term goal of a security strategy, for instance, cannot be to outsmart criminals, since that will only breed smart criminals. (In the short term, there are plenty of tactical occasions when one must struggle to outsmart bad guys, of course. The strategic goal has to be to change the game theory landscape so that motivations for creepiness are reduced. That is the very essence of the game of civilization. (p.311)

Suppose, though, that any cloud computer operator, whether it is a social network, an eclectic Wall Street scheme, or even a government agency, is required to pay you for useful data that is derived from you. Any Siren Server will then have a full-fledged commercial relationship with you. You will have intrinsic, inalienable commercial rights to data that wouldn’t exist without you. (p.317)

Once the data measured off a person creates a debt to that person, a number of systemic benefits will accrue. For just one example, for the first time there will be accurate accounting of who has gathered what information about whom. No amount of privacy and disclosure law will accomplish what accounting will do when money is at stake. (p.319)

But commercial rights would be tractable. Every photo of you would be registered not only in photographers’ accounts, but also in yours. There would then be duplicate records, as there always are in business, so that fraud would become nontrivial. (p.320)

Meanwhile, the police will be able to leverage the consistency of cloud-monitored physicality to detect criminal schemes. As pointed out earlier, you can fake an ID, but you can’t fake a thousand concurrent views of the person you are falsely pretending to be. The police will have to pay to access those views, just as they have to pay for cars and bullhorns these days. Policing should never be “free” in a democracy. All things must be balanced. (p.321)

Singularity University is part of a grand scheme. Most techies are not great showmen, but whenever the combination appears, watch out. (p.327)

If you structure a society on not emphasizing individual human agency, it’s the same thing operationally as denying people clout, dignity, and self-determination. (p.328)

We are witnessing the beginning of a new kind of death denial. … This in an intimate matter, and I’m loath to judge what other people do about their dead, but I do feel it’s essential to point out that when we animate the dead, we reduce the distinction we feel with the living. (p.329)

Given all this, I was quite surprised when one day this fellow said to me, “Capitalism is only possible because of death.” He had been visiting with some of the many researchers on the circuit of cyber-insiders who think they can solve the problem of death faily soon. Genes modulate aging and death, and those genes appear to be tweakable. Death, he explained, is the foundation of markets. This line of thinking is obvious and perhaps it’s not necessary to state it, but: That people age and die is what makes room for new people to find their places, so that aspiration is possible. (p.329)

Nonetheless, to get people to agree to pay to care for each other in advance requires political genius. Maybe it helps if everyone looks similar. Homogeneous societies seem to have an easier time of it. A common enemy doesn’t hurt, either. The online world fails miserably at providing any such traditional inspirations. (p.337)

It is never true that there is no top-down component to power and influence. Those who cling to the hope that power can be made simple only blind themselves to the latest forms of top-down power. (p.344)

The whole supposedly open system will contort itself to that Siren Server, creating a new form of centralized power. Mere openness doesn’t work. A Linux always makes a Google. (p.344)

Putting oneself in a childlike position is only an invitation to someone else to play the parent. (p.344)

This might rub a lot of people the wrong way; bottom-up, self-organizing dynamics are so trendy. But while accounting can happen locally between individuals, finance relies on some rather boring agreements about conventions on a global, top-down basis. (pp.344-345)

There’s a romance in that future, especially for hackers, and it seems to be the future most envisioned in techie culture. It comes up in science fiction constantly: The hacker as hero, outwitting the villain’s computer security. But what a crummy world that would be, where screwing up something online is the last chance at being human and free. (pp.345-346)

The CEOs will gather at the golf resort and talk about a core financial problem: In the long term the economy will start to shrink if they keep on making it “efficient” only from the point of view of central servers. At the end of that line there will eventually be too little economy to support even CEOs. How about instead growing the economy? (p.349)

It amazes me that traditional book publishers don’t understand the emotional value of paper, however. They are still trying to sell a one-price-fits-all consumer product in a gilded age, and thus are missing out on the obvious business opportunity under their noses. (pp.354-355)

Information always underrepresents reality. (p.364)

One good test of whether an economy is humanistic or not is the plausibility of earning the ability to drop out of it for a while without incident or insult. Wealth and dignity are different from a Klout score. They are states of being, not instant signals. (p.365)

Since I don’t use social media, I presumably have a Klout score of zero, which ought to be the superlative status symbol of our times. (p.365)

It can be doubly tricky because the way people talk about conformity is often as though it were a form of resistance to conformity. It is exactly when others insist that it’s a sign of being free, fresh, and radical to do what everybody’s doing that you might want to take notice and think for yourself. (p.366)

I miss the future. We have such low expectations of it these days. (p.366)

![[Caen; secure?]](https://maverisk.nl/wp-content/uploads/dscn8296.jpg)

[From the brewery, towards the future]

[From the brewery, towards the future]