[Or a mess, when addressed too formally]

Yet another ‘Book By Quote’ then (An attempt to subjectively summarise a book by the quotes I found worthwhile to mark, to remember. Be aware that the quotes as such, aren’t a real unbiased ‘objective’ summary; most often I heartily advise to read the book yourself..!)

So, this time: Henry Mintzberg’s Managing, Pearson Books, 2011, ISBN 9780273745624.

Bramwell Tovey of the Winnipeg Symphony Orchestra stepped off his podium to talk about the job. “The hard part,” he said, “is the rehearsal process,” not the performance. (p.5)

The more we obsess about leadership, the less we seem to get. (p.9)

After years of seeking Holy Grails, it is time to recognise that managing is neither a science nor a profession; it is a practice, learned primarily through experience, and rooted in context. (p.9)

But effective managing is more dependent on art, and is especially rooted in craft. (p.10)

Most of the work that can be programmed in an organization need not concern its managers directly; specialists can do it. That leaves the managers with much of the messy stuff – the intractable problems, the complicated connections. (p.10)

The Internet may be driving much management practice over the edge, making it so frenetic that it has become dysfunctional: too superficial, too disconnected, too conformist. (p.40)

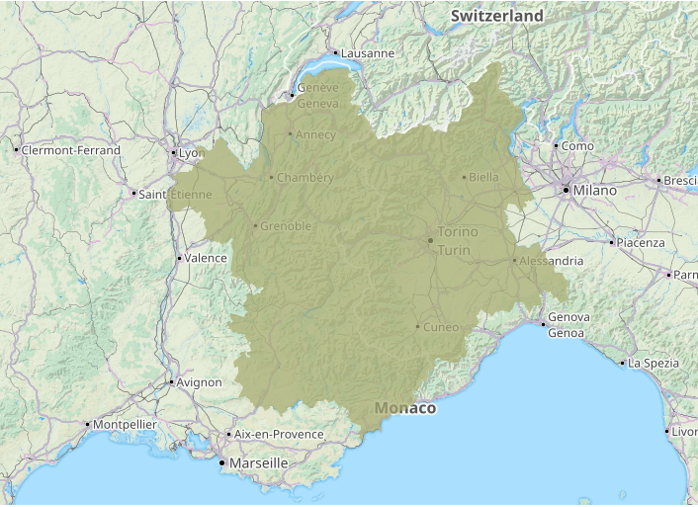

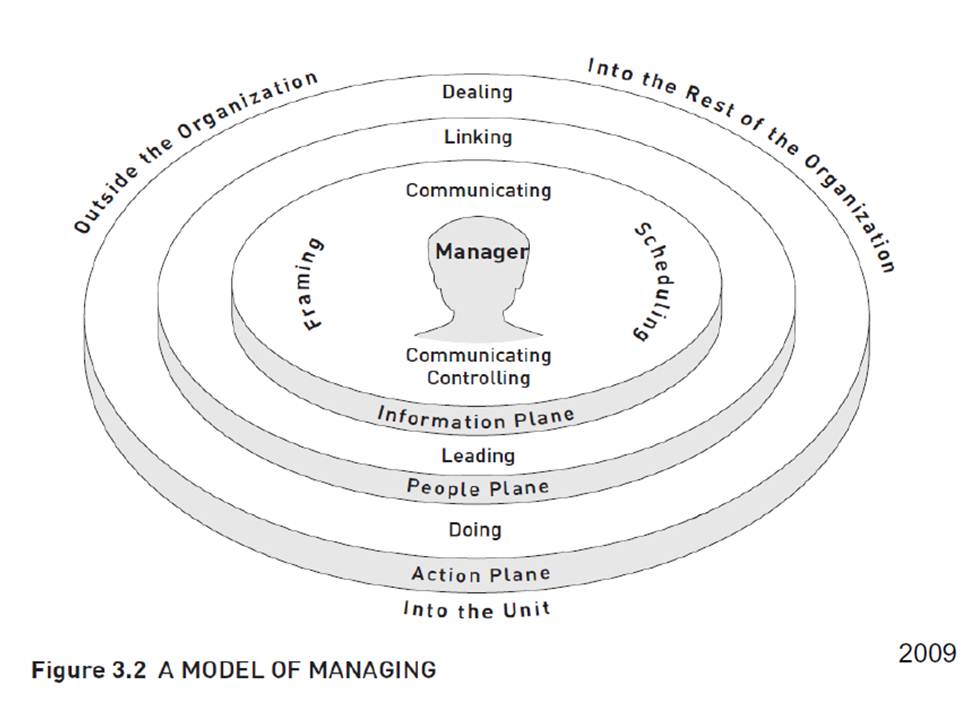

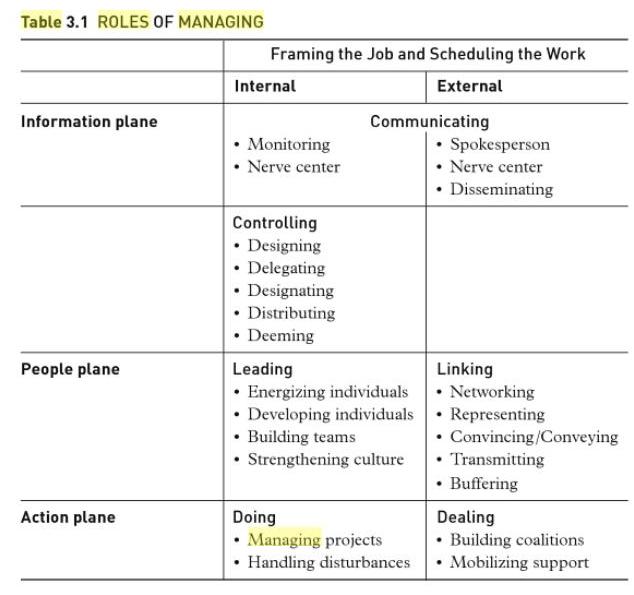

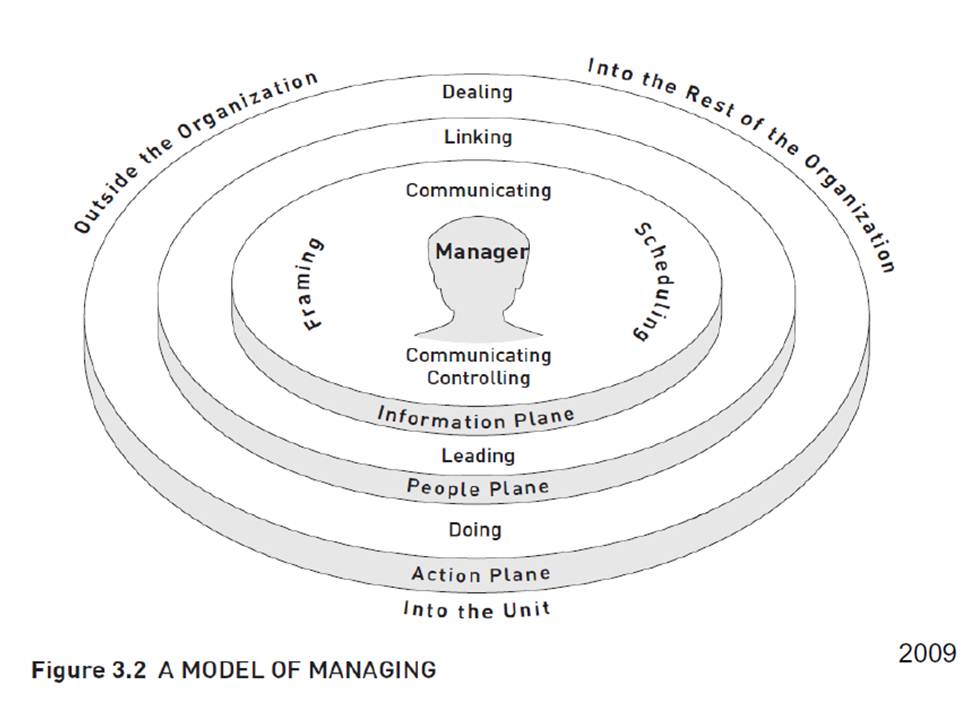

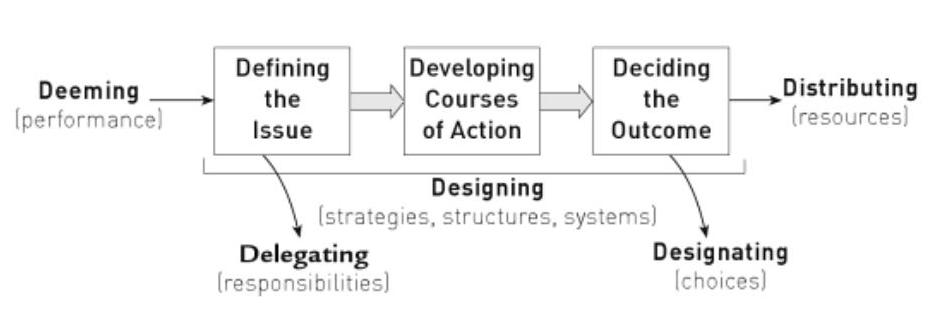

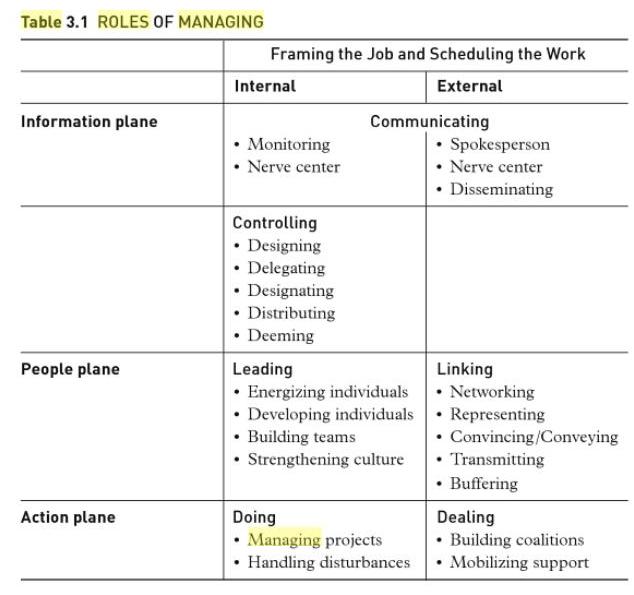

… depicting management as taking place on three planes: information, people, and action, inside the unit and beyond it. (p.43)

Let me consider two possible explanations. The first is that, as in other primitive societies, we live in mortal fear of our own gods, or at least our own myths, and management/leadership is surely one of them. Perhaps we fear the consequences of revealing their nakedness, or our own. Of course, we write about “leadership,” ad nauseam, but little of that touches on the everyday realities of managing. (p.46)

A good part of the work of managing involves doing what specialists do, but in particular ways that make use of the manager’s special contacts, status, and information. (p.47)

As Whitley put it, managing is “not so much focused on ‘solving’ discreet, well bounded individual problems as in dealing with a continuing series of internally related and fluid tasks”… (p.51)

Imagine biology with no vocabulary to discuss species: how to distinguish, for example, beavers from bears without any word beyond mammal? This is the state we are in when it comes to organizations, in practice as well as in research: we have little vocabulary beyond the word organization. (p.106)

• The Entrepreneurial Organization: centralized around a single leader, who engages in considerable doing and dealing as well as strategic visioning

• The Machine Organization: formally structured, with simple repetitive operational tasks (classic bureaucracy), its managers functioning in clearly delineated hierarchies of authority and engaging in a considerable amount of controlling

• The Professional Organization: comprising professionals who do the operating work largely on their own, while the managers focus more externally, on linking and dealing, to support and protect the professionals

• The Project Organization (Adhocracy): built around project teams of experts that innovate, while the senior managers engage in linking and dealing to secure the projects, and the project managers concentrate on leading for teamwork, doing for execution, and linking to connect the different teams together

• The Missionary Organization: dominated by a strong culture, with the managers emphasizing leading to enhance and sustain that culture

• The Political Organization: dominated by conflict, with the managers sometimes having to emphasize doing and dealing in the form of firefighting (pp.106-107)

… “downsizings.” This looks to be a contemporary form of bloodletting – the cure for every corporate disease. (p.111)

In other words, pressure in this job is business as usual – … managing is “one damn thing after another”. Brian Adams of Bombardier was not in a classical job of “managing by exception”; his was a job of the management of exceptions. (p. 116)

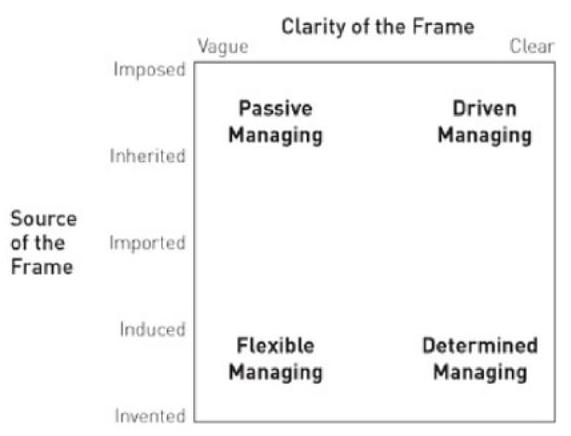

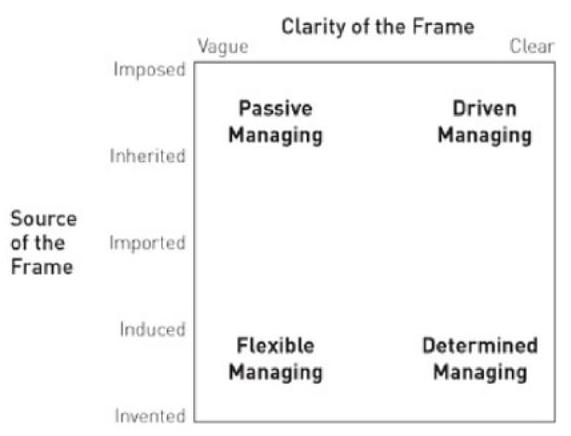

If one factor stood out in these days of observation, it was proactiveness : the extent to which the managers used whatever degrees of freedom available for the benefit of their units or organizations, even if that was to reinforce stability. (p.122)

This assumption, that we can change our behaviours the way we change our golf clubs – a long-standing one in much of applied psychology and management development – needs to be scrutinized. (p.131)

The effective manager may more usually be the one whose natural style fits the context, rather than the one who changes style to fit context, or context to fit style (let alone being a so-called professional manager whose style is supposed to fit all contexts). (p.132)

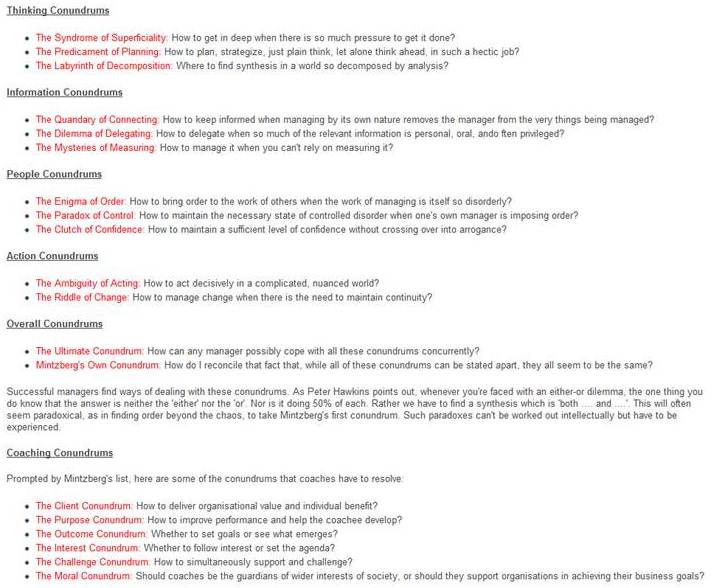

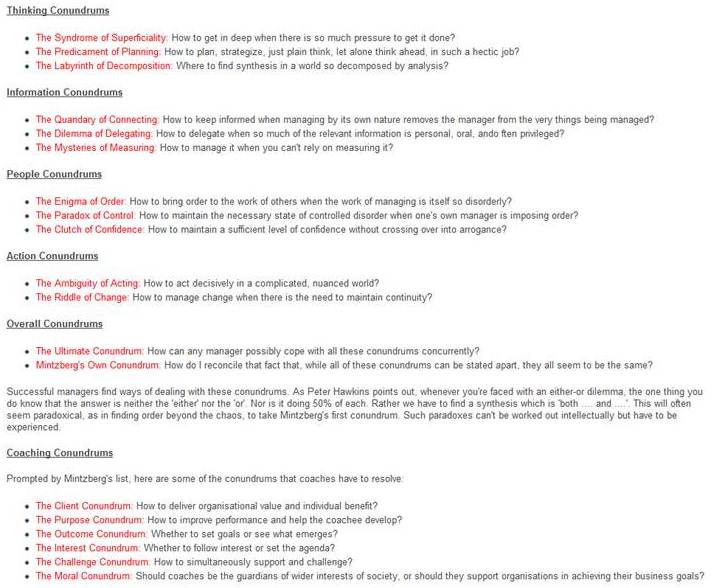

If such questions could be resolved simply, they would go away. They remain because they are rooted in a set of conundrums that are basic to managing – concerns that cannot be resolved. In the words of Chester Barnard: “It is precisely the function of the executive … to reconcile conflicting forces, instincts, interests, conditions, positions and ideals”(1938:21). Notice his use of the word reconcile, not resolve. (p.158)

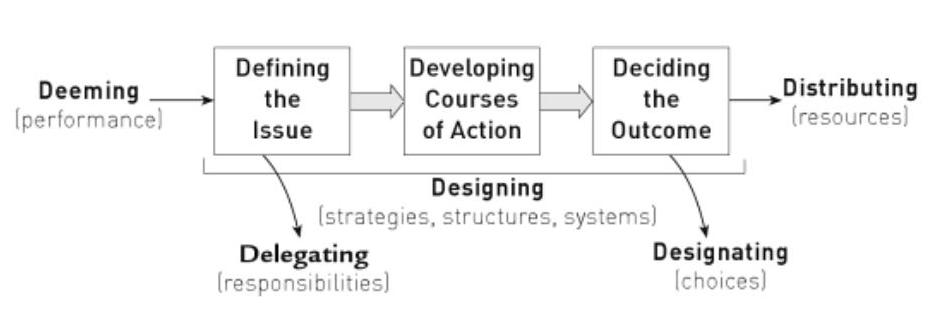

Hence … the job of managing does not develop reflective planners; rather it breeds adaptive information manipulators who prefer a stimulus-response milieu. (Mintzberg 1973:5) (p.160)

Given the dynamic nature of their job, managers have to find time to step back and out; this has to become intrinsic to their work. Reflection without action may be passive, but action without reflection is thoughtless. (p.160)

When Michael Porter wrote in The Economist that “I favour a set of analytic techniques to develop strategy” (1987), he was dead wrong: Nobody ever developed a strategy through a technique. (p.162)

Strategies are not tablets carved atop mountains, to be carried down for execution; they are learned on the ground by anyone who has the experience and capacity to see the general beyond the specifics. Remaining in the stratosphere of the conceptual is no better than having one’s feet firmly planted in concrete. (p.163)

Structure is supposed to take care of organization, just as planning is supposed to take care of strategy. Anyone who believes this should find a job as a hermit. (p.164)

Nothing is more dangerous in an organization than a manager with little to do. (p.165)

Common these days is what can be called the administrative gap. … A gaping hole exists between those who administer and those who deliver the basic services. (p. 171)

“Top management’s insistence [at a teleconference “far removed from the world of murky technology, shims, improvisation, and tacit understanding that engineers used to make the shuttle fly”] on explicit argument as a substitute for their own lack of firsthand experience silenced te tacit reservations that foreshadowed tragedy”(Weick 1997:395) (p.173)

It has become a popular adage that if you can’t measure it, you can’t manage it. That’s strange, because who has ever really measured the performance of management itself? I guess this means that management can not be managed. … Apparently we have to get rid of both management and measurement – thanks to measurement. (p.176)

1. Hard data are limited in scope. They may provide the basis for description, but often not for explanation. (p.177)

2. Hard data are often excessively aggregated. … It’s fine to see the forest from the trees – unless you’re in the lumber business. Most managers are in the lumber business: they need to know about the trees, too. Too much management takes place as from a helicopter, where the trees look like a green carpet. (p.177)

… we have to cease being mesmerized by the numbers and stop letting the hard information drive out the soft, instead combining both whenever possible. (pp.178-179)

As Tom Peters put it, in managerial work “’sloppiness’ is normal, probably inevitable, and usually sensible” (1979:171) (p. 180)

The organization may need predictability, but the world has this nasty habit of sometimes becoming unpredictable: … (p. 180)

Hierarchies work in both directions, so what is sent down has a habit of coming back up, and when a manager imposes a nice neat plan and gets back nice neat reports – on how nicely and neatly the plan was supposedly executed. (p.181)

In other words, managers often have to feign confidence. For reasonably modest managers, this can be difficult enough; for the supremenly confident, it may not be difficult at all, just catastrophic. (p.186)

If you are sure of the facts and are positive of the right corrective action to be taken, if you endorse any single answer, you’re dead. (Pascale and Athos, p.188)

… succesful managers are flawed – we are all flawed – but their particular flawsare not fatal, at least under the circumstances. (p.197)

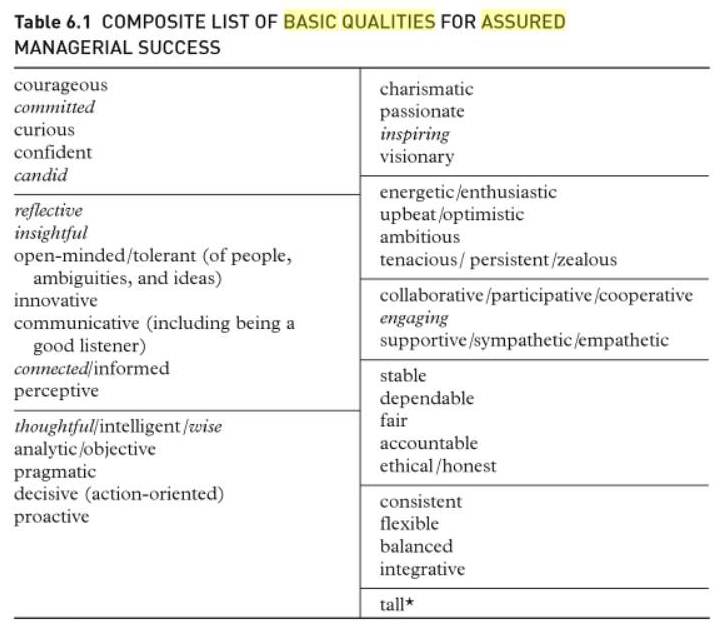

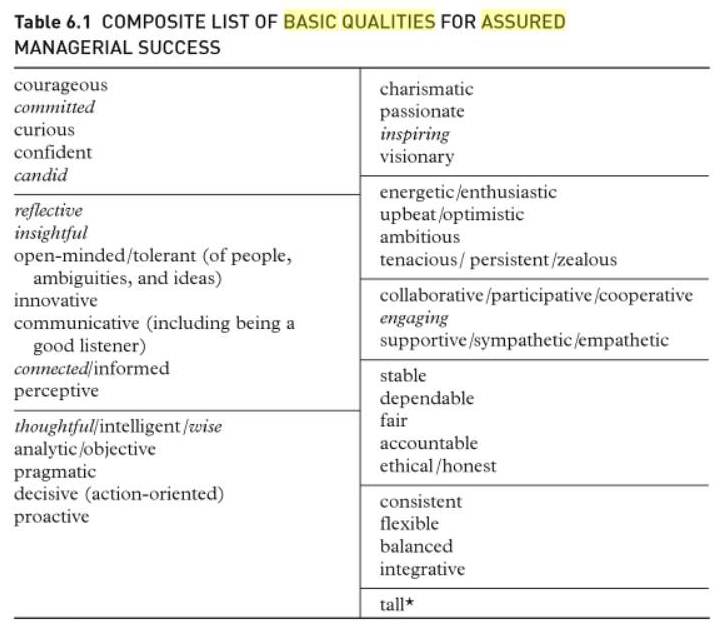

Fatally flawed are those superman lists of managerial qualities, because they are utopian. (p.198)

That is why the terms “calculated chaos” and “controlled disorder” apply so well to managerial work. (p.210)

To appreciate other people’s worlds does not mean to invade their privacy or to “mind-read” them, which can be condescending. Lewis et al. found these to be “destructive characteristics” seen only in “the most severely dysfunctional families” (p.213). (p.213)

Hiro Itami …told the participating managers: “Management is not to control people. Rather it is to let them cooperate.” (p.213)

Collaboration is not about “motivating” or “empowering” people in the unit, because as noted earlier that may just reinforce the manager’s authority. It is rather in helping them, and others outside the unit, work together … (p. 214)

Managing seems to work especially weel when it helps to bring out the energy that exists naturally within people. It is important to appreciate that there is nothing especially magical about this thread, no great characteristic of leadership. (p.214)

Mary Parker Follett wrote in 1920 that “the test of a foreman is not how good he is at bossing, but how little bossing he has to do.” (p.215)

Managers who try to go it alone typically end up overcontrolling — issuing orders and deeming performance in the hope that authority will ensure compliance. (p.215)

To quote Isaac Bashevis Singer in what could be a motto for the effective manager: “We have to believe in free will; we’ve got no choice.” (p.216)

Effective managers thus do not act like victims. They are “agents of change,” not “targets of change”. (p.216)

Managing is a tapestry woven of the threads of reflection, analysis, worldliness, collaboration, and proactiveness, all f it infused with personal energy and bounded by social integration. (p.217)

Managers should be selected for their flaws as much as for their qualities. (p.219)

Managing happens on the inside, within the unit (with the roles of controlling, leading, doing, and communicating), and on the outside, beyond the unit (through the roles of linking, dealing, and communicating). Yet it is usually people outside the unit who control the selection of its manager … What sense does this make, especially when it is so much easier to impress outsiders, who have not had to live with the candidates on a daily basis? Charm may be one criterion for selection, but hardly the main one. (p.220)

If one simple prescription could improve the effectiveness of managing monumentally, it is giving voice in the selection processes to those people who know the candidates best – namely, the one who have been managed by them. (p.220)

There seems to be some tendency of late, at least for senior positions, to favor outsiders: the new broom that can sweep clean. Unfortunately, the sweeping may be done by the devil the selection committee does not know, while the sweeper may not know enough to distinguish the real dirt. So the danger arises, especially in this age of heroic leadership, that the new broom will sweep out the heart and soul of the enterprise. (p.221)

Managers are not effective, Matches are effective. (p.222)

Maccaby does add that “a visionary born in the wrong time can seem like a pompous buffoon.” (p.222)

A healthy organization is not a collection of detached human resources who simply look after their own turf; it is a community of responsible human beings who care about the entire system and its long-term survival. (p.223)

A society that is based on the letter of the law and never reaches any higher is taking very scarce advantage of the high level of human poossibilities. The letter of the law is too cold and formal to have a beneficial effect on society. Whenever the tissue of society is woven of legalistic relations, there is an atmoshpere of moral mediocrity, paralyzing man’s most noble impulses. (Aleksander Solzhenitsyn, p.224)

Executive impact has to be assessed in the long run, and we don’t know how to measure performance in the long run, at least as attributable to specific managers. So executive bonuses should be eliminated. Period. (p.225)

Sure, measure what you can. But then be sure to judge the rest: don’t be mesmerized by measurement. Unfortunately, we so often are, causing us to drive out judgement. (p.224)

To be effective in any managerial position, tere is a need for thoughtfulness – not dogma, not greed risen to some high art, not fashionable technique, not me-too strategies, not all that “leadership” hype, just plain old judgement. (p.226)

“Consider a book you read recently [may not apply to many today’s managers, ed.]: can you quantify its costs?” Sure: so much money to purchase it, so many hours to read it. “Good. Now, please quantify the benefits. If you can do that – measure its impact on you – please let me know and I will do the same for the program.” (p.226)

Managers, let alone leaders, cannot be created in a classroom. (p.227)

Most management education and much management development is organized around the business functions. This is fine for learning about business, but marketing + finance + accounting, etc., does not = management. (p.229)

Management is a very practical, down-to-earth activity. There are no profound truths about it to be discovered and there are no hidden secrets to be uncovered about how to do it. Management is a very simple activity which involves bringing together people and resources to produce goods or services .. The message is to lighten up a bit – be playful, agile, and alert. (Watson 1994:215-216; p.234)

![[Caen; secure?]](https://maverisk.nl/wp-content/uploads/dscn8296.jpg)