On how Risk Management is self-defeating… or just something one has to do while Life has other plans with you(r organization).

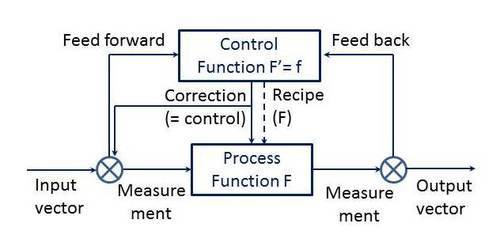

First, the übliche picture:

[Shadow (play) of Dudok, Hilversum again of course]

First, the Defeating part. This, we hardly discuss at length, full enough, but when we do, it’s so obvious you understand why: Because RM is about cost avoidance, even if opportunity cost avoidance. Which makes you the Cassandra, the Boy Cried Wolf of the courtiers (sic). It’s just not interesting, not entrepreneurial enough. [Even if that would be pearls before swines…]

Second, this is why it’s so hard to sell (no quotes, just outright sell for consultancy or budget bucks) the idea of RM to executives – they only see the cost you are. They don’t see themselves as delivering something if, if, if only, they had integrated RM into their daily ‘governance’ (liar! that’s just management!) / management. They don’t want to do anything. They just don’t understand to do something that doesn’t show to be effective even if others for once see no harm (though the others will not even care to flag the kindergarten-level window dressing that’s going on with the RM subject; too silly that, to call out).

Third, this happens not only with ‘boardroom’ RM (~consultancy/advisory), it has been well-established at lower ranks; all the way from the mundane IT security, Information Security, Information Risk Management, Operational Risk Management (where the vast majority of organisations don’t make anything tangible anymore), including the wing positions of, e.g., Credit and Market Risk (which are in fact, with the visors to mention, the same as the previous!), to Enterprise Risk Management altogether.

Fourth, we tie in Queuillism. The Do nothing part almost as in Keynesianism where in the latter, future-mishap prevention should be arranged during the years where government intervention wasn’t required as such. As in Joseph’s seven fat years contra the seven years of famine (Genesis 41). How does this reflect on RM? Would it not be just BCM in its widest, enterprise-wide sense? Isn’t that what ‘management’ is about, again..? Just sanding off the rough edges and for the rest, give room to the actual stars, the employees at all levels, to let them bring out their best – so exponentially much more than you can achieve by mere, petty, command & control. You raise KPIs, I rest my case of your incompetence. And this goes for governments even more. Just enormously expensive busywork.

Fifth, finally, the fourth trope points into the direction of Machiavelli’s Fortuna. Which was also covered by Montaigne, of course. It doesn’t matter what you do, in the end, Life has other plans with you. Sobering, eh? Oh but again, you can shave off the rough edges for yourself, too. Just don’t think in the end, that will matter much beyond some comfort to you. Katharsis, and move on.

OK, since you held out so long:

[The same, from another angle]